با برنامه Player FM !

Jan Senbergs

Manage episode 388546878 series 1255162

Above photo of Jan Senbergs by Riste Andrievski

Click play for my podcast introduction to this interview and scroll down for the transcript.

Podcast listeners click here and scroll down for transcript.

Watch the YouTube video of Jan Senbergs’ studio and work here

Links

- Jan Senbergs’ website

- Jan Senbergs on Instagram

- Jan Senbergs at Niagara Galleries

- Talking with Painters YouTube channel

- Talking with Painters on Instagram

- Talking with Painters on Facebook

- Subscribe to the TWP newsletter

- PDF version of transcript for tablet/desktop

With over six decades of work as a painter, printmaker and draughtsman, leading artist Jan Senbergs has exhibited in over 50 solo shows and has been the subject of three survey shows including a major retrospective curated by the National Gallery of Victoria in 2016. A rare accomplishment.

His art evolved from early masterly screenprints to large scale paintings and with subject matter as varied as urban and natural landscapes, industrial themes, surreal structures and forms and aerial map-like works.

This episode has been a long time coming. Covid threw out our plans for an early 2020 meeting but two years later we met in Jan’s inspirational studio in Melbourne. His voice has been affected by some health issues and so this episode is coming to you by way of transcript (below) and an intro on the podcast.

As I was setting up my audio equipment on the day of the interview, Jan and I chatted about the time he had spent in London in his 20s. We talked about other Australian artists who were there at that time. That’s where the recording of the interview began.

Jan Senbergs

I was the younger artist who came into that area and I didn’t know anybody. I didn’t want to bother the local Antipodeans (laughs) so I usually went out by myself. I headed for the National Gallery on one occasion and ran into Arthur Boyd heading there too. We travelled together on the bus from Pimlico to Trafalgar Square. It was very nice because we walked through the Gallery making comments. It’s lovely to do that with another painter. We walked past one room and Arthur stopped and said, ‘There’s a good painting in this room.’ It was a big dog watching over a dying nymph, by Piero di Cosimo. He was such an interesting painter. Afterwards, Arthur suggested we go and have a drink, so we went across the road and had a couple of beers and then he said ‘You’ll have to excuse me, but I’ve got to go back home. I’ve got a few duties there.’ We shook hands and I never saw him again.

Maria Stoljar

You never saw him again?

JS

No, but what was nice about it was the generosity of the older person to somebody younger who had just arrived.

MS

How lovely. But you knew a lot of famous Australian artists like Fred Williams, for example. He was a friend of yours, wasn’t he?

JS

Yeah, I knew Fred. When I first started showing around, I mixed with some of the older artists. At that time there were hardly any younger artists around. And because I hadn’t gone to an art school, I was very isolated. It’s quite different for artists today. Now there are thousands of young people trying very hard to make good art after their schooling. It’s a different atmosphere. Schools pump out all these people with hopes and ambitions. That’s the reason it’s good to know some of the older painters.

MS

Yes. Like John Brack?

JS

Yes, John Brack was one … Len Crawford, Fred, Roger Kemp – these were heavy-duty Melbourne blokes.

MS

It’s amazing that you, in your early 20s, were hanging out with those people.

JS

Yeah, it was actually. Because I couldn’t get into art school so I’d started working in a silkscreen printing company, which was a terrible bloody job (laughs).

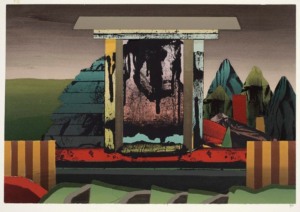

‘Modern monument in colour ‘ 1975,

Colour screenprint, 56.6 x 81.2cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

MS

Why? Was it heavy work or just dirty work?

JS

Dirty work. Screenprinting was very dirty. It was toxic and unventilated. As an apprentice you’ve got to scrub the screen and so on – you get all the shit jobs (laughs), but that’s understandable.

On Friday nights, though, during the period of the six o’clock closing, I used to go into town. I didn’t want to go with the local trades blokes and drink with them, I’d go straight into Little Collins Street where all the real old lefties hung out – a fantastic atmosphere. They weren’t all painters by any means – there were writers, clapped-out academics and all sorts of people.

MS

Really bohemian.

JS

Yeah, but interesting to me. I went there and I just stood around. They didn’t pay any attention to me, but I was listening. It was an education. A political education as well.

MS

How amazing. So did you keep in contact with those people?

JS

Well, most of them I did, yeah. Including some writers. I was always interested in writing and writers. I used to read a lot when I was younger. The usual standard fare of James Joyce (both laugh).

So I was mixing with all these people at six o’clock closing. There was a frantic atmosphere on a Friday night. There were all these characters coming in from work, and they wanted to have debates and bash out the things that they wanted to talk about. It was interesting.

MS

Yeah, and do you feel like that sort of political leaning comes through in your painting? Do you consciously think about that?

JS

No. I mean, it’s there. How can I put it? I don’t like to be a spruiker for any cause. Your paintings should do that. Usually what happens is that if people are too strident in their political views, they produce paintings which are very single-minded – with a message they want to send, but often the artworks are no good. There’s always been a debate about that, to see how far you can go.

MS

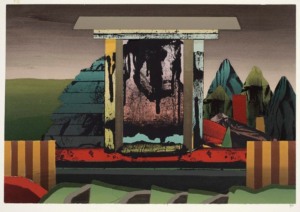

Actually what comes to mind are the ‘Altered Parliament House’ works. Those two works you painted when you were in Canberra. You were there during the dismissal of the Whitlam government in 1975. They’re powerful paintings which are silkscreen and oil. Can you tell me a bit about that time?

‘Altered Parliament House I’ (1976) Synthetic polymer paint and oil screenprint on canvas Collection: National Gallery of Victoria

JS

I was in Canberra at the ANU for a couple of years. What do they call it? Creative Arts Fellowship. They gave me a studio. Students were supposed to come and listen to your wise words but nobody turned up so it was a very easy job (laughs). And a very interesting period because at that time the Whitlam Government was introducing Medicare. I used to go to Parliament House and sit listening to Question Time. I’d wander up there out of curiosity, to see what they were talking about – to see how they were misbehaving (laughs). It was fascinating, it was lively. Then the day came when Gough was overthrown. The two paintings I did were of Parliament House (the Old Parliament House). They were sort of on a dark ground. It was nighttime. I was living in Campbell which crossed Anzac Parade and in the distance you could see this white ghost-like structure that was Parliament House. It gradually became a kind of symbol, or the anchor, for the paintings. They’re about as close as I’ve ever been to a political painting – I like to leave that sort of thing with a suggestion rather than hammering it down somebody’s throat.

MS

I think one is in the National Gallery of Victoria and the other is in the National Gallery in Canberra. With respect to number one, in the foreground there are ruins and so it’s like a metaphor for the destruction of the whole parliament in a way?

JS

Yeah, it did have those suggestions. Everybody was very keen on what was happening politically at the time and so you didn’t need to sort of push your point. Politically, I’ve been towards the left all the time, but at the same time I’m very critical and I’m becoming more critical as I get older! (laughs)

MS

What I find interesting about your work is the fact that you started off in silkscreen printing and even though you let that go by about 1980 or so, you started incorporating that into your painting.

JS

That’s true, yeah.

MS

That sounds like a quite laborious thing to do.

JS

It was a shocking thing. I hated it by the end of it. (laughs)

MS

(laughs) Did you? Why?

JS

Oh, it was so laborious to get things right, setting up the registration over large areas. It was very hard work. It wasn’t like when you’re painting or doing a drawing. When I came back from Canberra, I was doing screen prints and I felt at that stage that I was getting a bit too sophisticated with the prints – too much of a smartarse (laughs) – so I gave it away.

‘The flyer’ 1975

Synthetic polymer paint, oil screenprint on canvas, 167 x 244cm

Collection of Paul Guest, Melbourne

MS

I think by that time you were being called ‘the greatest silkscreen printer in Australia’. Maybe that was when you felt like you had had enough?

JS

Well, I don’t know about that. But what I wanted to do was to make a mark again, go completely the other way. So I began to draw. And I started to draw around Port Melbourne, especially old Port Melbourne. I gradually changed.

Port panorama, 1980, lithograph, printed in black ink on white BFK Rives Moulin du Gué paper

45.4 x 63.4 cm image; 57.0 x 76.0 cm sheet

Collection: Art Gallery of NSW

MS

So that was quite an industrial sort of landscape?

JS

Yes. And that was also around the time that I met my second wife Helen Beresford.

MS

Yeah.

JS

All of these things – it was a very exciting time.

MS

It must have been a really big change in your life.

JS

It sure was, yeah.

MS

And it was around that time that you got that huge commission to create a work for the High Court of Australia. I think you were involved from the very beginning when they were designing that building. Just to give a bit of background – the High Court of Australia is a great example of brutalist architecture. We’re talking about huge concrete walls, big open spaces, and the area that you had to create a work for was quite a large area.

JS

In the atrium, yeah.

MS

So how did you go about that?

JS

They had a shortlist of about four or five when they gave me the job. I think they probably gave it to me because I’d realised it was too huge an area for canvas – it would sag within a couple of years – so I’d thought of some other material. I started through theYellow Pages to look for materials. I didn’t get very far! I spotted ‘aluminium’. That was it! (laughs) Aluminium was light and it was permanent, you had to anodise it, it wouldn’t corrode.

Constitutional Wall Mural and States Wall Mural 1977 – 80

Collection of the High Court of Australia

MS

Had you ever used it before?

JS

No

MS

So this was a totally new technique that you were going to try?

JS

That’s right. I had a friend, Ian Claremont, who knew about anodising. It was all a bit unexpected. I told the story of the Constitution of the High Court, the States and the Supreme Court with images etched into the aluminium.

MS

So the brief was basically to depict imagery about the Commonwealth and the six states. Is that right?

JS

They didn’t mention the six states but that became part of it. I introduced that.

When I first got the job, I knew nothing about the High Court and I wondered ‘What the hell am I going to do? What sort of design?’

MS

(both laugh) Well, I think before the building was built, the High Court was sitting in Melbourne and Sydney. There was no building in Canberra?

JS

That’s right. The High Court had rooms in every state – small rooms, chambers. In order to find out more about what the function of the court was, I was lucky enough to meet Ninian Stephen, who used to be the Governor-General and a High Court Judge. I asked him if I could come and see him to explain what the functions of the High Court were.

MS

(both laugh) Well, I mean, when you think about it, the layman wouldn’t know what the High Court did.

JS

Ninian Stephen was so tolerant and kind to me. He carefully explained how the High Court worked. Then I had to design it. The logistics alone were a challenge. I was worried the whole thing would slide off the wall – so I designed these boxes and I screen printed images on them. There was the Constitutional wall and the States wall, shooting all the way up to the top.

MS

And how did you come up with the imagery? What were you looking at?

JS

Well, by that time I was looking at various symbols of Australian institutions. In the case of what I call the States wall, I had all sorts of symbols from each state. For example, Queensland had a tropical industry, sugar cane, which told a story. The larger Constitutional wall was to do with things from the time of Federation when Australia became a state in its own way – a changeover from the British way – so there are a lot of images there. And they liked it (laughs). I found an anodising factory in Melbourne. When it finished for the day, Ian and I would go there through the night and etch the big aluminium sheets in huge acid baths before the factory began its morning shift.

MS

It’s fantastic and it’s still there, obviously. And I think the Queen came when they opened the High Court, and didn’t you have an exchange with her?

JS

I did, actually. When we finished the job and the time came to open it, we were all lined up and the Queen and Prince Philip came along, with the Chief Justice Garfield Barwick introducing us. When the Queen got to me she looked up at my piece and she said, ‘My, that’s big.’ I said, ‘Yes, Ma’am’. The Duke was about four paces behind, and he came up and said, ‘Do you do this kind of thing often?’ and I said ‘Whenever I can’ (laughs). So that was my meeting with the Queen and the Duke.

MS

(laughs) That is a pretty amazing story. So let’s talk about other works of yours that I’ve found interesting. And one of them was when you went to Antarctica. What was that trip like?

JS

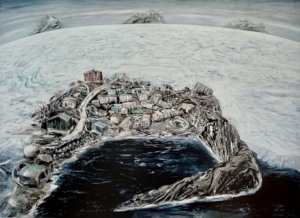

It was marvellous, wonderful. It was back in 1987. We went down with the Australian Antarctic Division’s resupply ship MV Icebird. It sailed out to Heard Island and delivered food and supplies to the Davis and Mawson stations. That was the main intention of the trip. It was marvellous too on all sorts of levels. The Antarctic landscape is fantastic and it’s been photographed a million times, but my angle was a bit different. I was fascinated with life down there and how we are squatting on another continent with our suburban values. My paintings were more about the bases than the icebergs.

MS

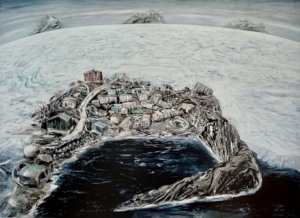

And you had two major paintings, ‘Mawson’ and ‘Davis’, depicting those bases down there where you gave us that aerial perspective that you’re very well known for – those map-like paintings. These aren’t the same as your more urban pictures but it’s that sort of feel, of an aerial perspective. And with all that ice in the background, these are very dramatic paintings.

‘Davis’ 1987

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas

213 x 289cm, private collection

‘Mawson’ 1987

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas

213 x 289cm, private collection

JS

Yes, the ‘Mawson’ painting is like that. You’ve got this settlement right on the edge with a huge dome of Antarctica behind it. I exaggerated it. There was a kind of map-like painting of a base as well as a huge amount of rubbish lying about. Part of the job was to pick up some of the rubbish and go and put it back on the ship and take it to a quarry in Tasmania.

MS

Oh ok, I didn’t realise that. That’s interesting because that idea of detritus and waste, that’s something that often appears in your work. Is that something that attracts you – those forms?

JS

I start off with images that I want to use. Then I apply some of them to paintings. It’s a combination of thinking. It’s hard to explain. It’s a kind of storytelling, only in a less obvious way. Firstly, I paint a quality of imagery, before I start telling the story–you know, that’s important. With Davis and Mawson, I wanted details of various things that I wanted to add to the composition – a bit like early Chinese landscapes that are taken from various levels – unlike the Western view on a fixed level. So you have various points of viewing all crisscrossing that make up the composition which you in turn take to the next step to make it interesting.

MS

Yeah. Would you start with a sketch to determine the composition?

JS

Yes. But also I had notebooks. I’d do sketches there. They were mostly sketches from memory. Plein air ones as well of course.

MS

And when you’re working on a big painting, do you ever decide halfway through ‘this isn’t working, I’ve got to change it’. Does that happen often, or have you really predetermined it before you start?

JS

You mean the composition?

MS

Yes.

JS

Sometimes. Sometimes you fail and you start from scratch again. But not often. For me, a lot of these canvases are like maps. I’d worked out the scale, the relationships. There’s a lot of fiddling around with map-like imagery early on.

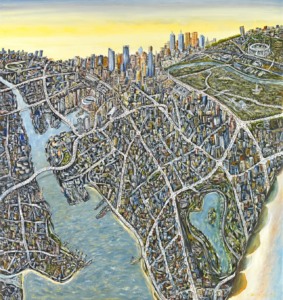

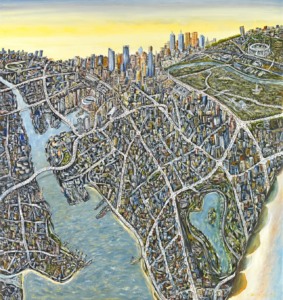

‘Melbourne capriccio 3’ (2009)

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 195.2 x 184cm

Collection: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

MS

I’d like to jump back now – so in 1966 you were awarded the Helena Rubinstein Travelling Art Scholarship and you went to Europe. You stayed in London for a while and then when you came back in the late 1960s, things had changed in the art world hadn’t they?

JS

They sure had, yeah.

MS

Can you tell me a bit about that? I think all the rage was colour field painting, hard edge abstraction …

JS

That’s right. When I came back there was this new type of thing here and so I wanted to show some of the smart tricks I learnt in London (laughs)

MS

(laughs) So, you found that you changed direction a little bit over that period?

JS

Yeah, I realised that my previous paintings were too clogged up, too rich sometimes, and also crude. I didn’t mind the crudeness but it was time to leave that. I’d grown up a bit (laughs). I made some steel sculptures, a kind of gesture at outdoor art, minimal art.

MS

They were quite geometric, weren’t they?

JS

Yes, standing on legs. They were about 20 feet tall. I made them in my backyard. I left the final processes to the fabricator but I made the design, a kind of slot to hold this image of a head, but the problem was the image was too top heavy (laughs).

MS

So they didn’t stay up?

JS

They stayed up for a couple of years, in St Andrews, in the hills north of Melbourne. I found some land to put this stuff on and met Cliff Pugh, who lived up there. He said I should contact Frank Dalby Davison. Dalby Davison was a very controversial and interesting writer in the ’30s, being ahead of the game and writing about people’s relationships. He agreed to put them up on his land, and I said I’d try not to make a mess (both laugh). I made five of these sculptures and dug a ditch and put them in concrete and left them there. You could see them from the road down below the hill and people were wondering what the hell they were.

MS

They looked sort of alien?

JS

Yeah, some people thought they were guideposts for planes coming in. People came up with all sorts of explanations for them.

MS

Isn’t that the definition of great art? To get people to wonder and to use their imagination.

JS

Exactly, yeah, that’s right. They stood up there for a while and then one day there was a huge storm and they blew over. Also, the cows didn’t help. Frank Dalby Davison had a lot of cows and they were leaning against the sculptures, causing them to topple, and I thought that was very unfair for Frank (both laugh).

MS

That’s a shame, but at least you’ve got images of them.

JS

Yes. I went back and saw Frank and said, ‘You’ve been very generous’.

MS

I bet he missed them because they would have been like a real statement on his property.

JS

Well, it could have been that. I suppose I was one of the first people doing that sort of thing in Australia. The Americans did that sort of land art– Robert Smithson and a couple of others, but in different ways. I had always wanted to do something outside of painting.

MS

And 3D obviously as well. But you didn’t continue to do a lot more of that sort of sculptural work?

JS

No, I stuck with the brushes.

MS

I want to take you back to when you first got to Australia. You had a rough time during the war years. What was it like when you got here?

JS

We left Latvia, ending up in the British sector after the war, in a DP (Displaced Persons) camp. We stayed there for about four or five years. And finally, we got boats to Australia. Nobody knew anything about Australia. For example, my grandmother who was with us carried a ham that she’d cured because she thought that in Australia there’d be no food (laughs). When she got off the ship the Customs officers took the ham. She was so upset – ‘They’ve taken away my food!’ (laughs). We were hauled off to Bonegilla, the migrant camp near Albury-Wodonga. It was an old army camp. All the adults were moaning and groaning but us kids loved it. I’d just turned 10 so I was very happy. It was like we were released from some dark place to this wonderful sky and golden grass, to muck around and enjoy all of it.

MS

So it was a very optimistic experience coming to Australia for you. You couldn’t speak English at that point?

JS

No. We lived there for about four months – my sister, mother, grandmother and I. The camp had people from all sorts of countries. We went to a one-teacher primary school for young farming kids – there were only about eight students. I often wonder how the local kids must have felt – their lovely little school invaded by hundreds of little wogs! (laughs)

MS

(laughs) What experience did you have with art at that point? How did you become interested in art?

JS

I was always drawing as a child. I went to trade school in Melbourne, at Richmond Tech – but I wasn’t at all interested in trades. I started to do little sketches in my exercise book. One day Len French the painter came to the school as a rookie teacher. He was a terrible teacher (laughs), but he used to liven the place up. One day he brought in three postcards: One was of saints, by El Greco, one was Cezanne’s ‘Mont Sainte-Victoire’, and the third was ‘The Sleeping Gypsy’ by Henri Rousseau. Len said, ‘Which one do you like?’. I liked Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy. And that triggered something in me because I began to realise that there was this other big world out there.

MS

He must have been a very exciting person to come into your life.

JS

He was, yeah.

MS

Was he an established painter at that point?

JS

No, he wasn’t. He was becoming established – he ran with the local scene. A couple of years before that he’d been overseas, he’d done a bit of travel, so he was sort of sophisticated.

MS

And he became a mentor for you for many years?

JS

He was in a way. He introduced me to the pubs (both laugh).

MS

Is that how you got to meet John Brack and Fred Williams and the other artists in Melbourne?

JS

The way I met John Brack was different. I had a studio in Hardware Lane – one of the lanes of Melbourne. It was an awful place, very dark and dingy, and I was doing these black, ugly pictures that nobody could possibly want (laughs). One day in walked John Brack with a bloke called Hal Hattam. He was a doctor who hung around with the artists and was a bit of a collector as well. Brack was very austere and firm, and I was like a rat scurrying around. They didn’t say much, just looked around and then left. But about two weeks later I was asked to drop a painting off at John Brack’s house – he’d bought one of my paintings. I was so touched.

MS

Wow.

JS

Because coming from him it was so special.

MS

Yes, and that’s before you actually got to know him?

JS

Yeah, he liked my stuff.

MS

He was a lot older than you, like 20 years older?

JS

He was, yeah. He came out of the army without firing a shot and then he became a teacher in Melbourne and got a job at the Gallery School at the NGV. He ended up teaching at Melbourne Grammar – all the little rich boys. (laughs)

MS

Well, they have to be taught too (both laugh).

JS

John Brack was a big influence on me because he was the conscience of our generation. Later, we shared the same dealer, Rudy Komon, who was my dealer in Sydney. George Baldessin was also with Rudy. As was Fred Williams. A bit of a boys’ club.

MS

Well, I suppose in those days there were fewer women artists. But that must have been a pretty amazing thing for you because Rudy Komon was one of the most influential art dealers in Australia at the time. He got you on his books when you were in your mid 20s I think?

JS

Yes, I was.

MS

That’s amazing.

JS

He was planning to give me a first show. But I’d gone and made a mess of myself – I sort of spoiled it all – I smashed myself up in a car accident. Went through the windscreen and almost lost an eye. Rudy came into the hospital and saw me and as he walked out, he said to someone, ‘Well it’s a pity about Jan, he could have been a good artist’ (laughs), and I said ‘Don’t say that!’

MS

I can imagine you didn’t want to hear that at that time. That didn’t happen in the end, thankfully!

JS

Years later when Rudy and I travelled around the place I sometimes raised that: I said, ‘Rudy, you almost wrote me off – you told me I was no good!’ He said ‘Oh, I wouldn’t do that to you.’

MS

So, you were with him for 20 years or so?

JS

Close to it yeah. He was quite different from the other dealers. He gave money to various painters from his stable.

MS

Like a wage sort of thing?

JS

Yeah, to keep them going. Rudy also had Jon Molvig from Queensland. Molvig would ring up Rudy and say, ‘Rudy I need some dough- not just some dough – the full symphony’. He was very keen on Molvig.

MS

And Rudy had a lot in common with you, didn’t he? Because he was also a migrant.

JS

He was, yeah. Though he never talked much about his past.

MS

He was a lot older than you.

JS

Oh, yeah. He was an interesting character. The first time I showed with him was in the ’70s. I was in a drawing show. When I came in from Melbourne to the gallery and saw red stickers everywhere. I said, ‘Rudy, Jesus! You mean all these people bought my drawings?’ and he said, ‘Oh yes, Jan, there are a few people who like you.’ But who they were he wouldn’t say. Years later, after he died, I was at Rudy’s gallery with Gwen Frolich. She was Rudy’s rock. She’d pulled him out of problems time after time – tax problems and all the other stuff – and she and I were looking through Rudy’s storeroom. We were digging through all this stuff when I came across one of my drawings. Then I found more of them, all from that first drawing show. And I said to Gwen, ‘What’s the story?’ Gwen just smiled and drew on a cigarette. She said, ‘Rudy thought you needed some money at the time.’ Rudy had bought up my drawings!

MS

And he did it that way so that it bolstered your confidence as well.

JS

Yeah, he was a good bloke. But he was full of bullshit as well (both laugh).

MS

Well, anyone in the art world has to be a bit like that don’t they?

JS

Yeah. I once travelled with him to South America, to the Sao Paulo Biennial, in which I was representing Australia. We went on this trip with James Gleeson.

MS

The famous surrealist painter.

JS

Yes, that’s right. Gleeson’s partner, Frank O’Keefe, wanted to go as well so it ended up being the four of us on a plane to Brazil, via Tahiti. Rudy wanted to go as our representative, but he really just wanted to be there for the trip.

MS

So for that 1973 Sao Paulo Biennial I understand you did 18 large paintings over two years. Those works were very typical of what you were doing at the time, those bleak industrial landscapes, very large works?

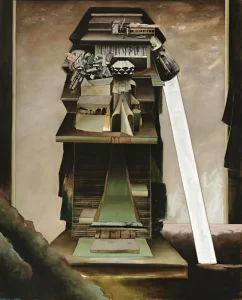

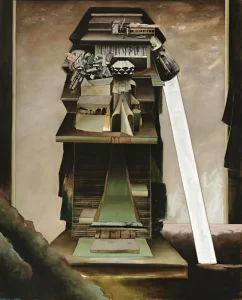

Fort 2 (1973),

152 x 183cm synthetic polymer paint, oil screenprint on canvas

Collection: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

JS

Yes, that’s right.

MS

And I think Fred Williams called you an ‘industrial surrealist’.

JS

(laughs) Yeah.

MS

Those structures and forms that are in those paintings – for example, ‘Fort 2’ – they do have quite a surreal quality to them. They don’t exist in the world. How did you come to paint those images?

JS

I was just starting to use silkscreen techniques in a painting, which straight away made everything much sharper. Even though you might have very dark colours, blacks and browns, there’s movement within those colours. People picked up on an industrial theme. People have sort of pigeonholed me as an industrial landscape artist. I’m not just that, I’m a lot of other things at the same time. But they like to label you – it’s always the case.

MS

Yeah. For example, those Antarctic paintings are totally different. Actually, those works where you were painting near your holiday home around the Otway Ranges in south-western Victoria, they’re also really beautiful works, and very expressive paintings.

‘Otway night’ 1994

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 198 x 259cm

Collection: Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney

JS

I’m glad you like them.

MS

And you know what I noticed about those and also the map paintings, those aerial paintings – they have much more colour. Did you find that you were using more colour later in your career?

JS

Yeah, I think so. I was slowly moving away from what I call my ‘axle grease’ period.

MS

(laughs) Which I liked as well.

JS

But you’re right. The colour change is there in the Otway paintings. It’s not over the top, but it’s there. I suppose as you get older you don’t have to hammer everything every time. You learn how to just step back, to retain your point. When you’re younger you’re fierce and attacking. As you get older it doesn’t matter so much. I’m finding that with me these days. I’ve had a very good run when I come to think of it – all the things that I’ve had the opportunity to do. It’s been marvellous. I’ve had the chance to do my own imagery, and I have always wanted to be outside the main movement. Maybe close to the movement sometimes, but not part of it.

MS

Why do you think that is?

JS

Must be my twisted nature (laughs).

MS

Yeah, well, I’m going to be a psychoanalyst now. Is it partly due to coming to Australia when you were 10, and not going to art school, not doing the traditional thing that somebody who was born here might have done?

JS

Yeah, sure. You become very aware of that of course, but you still want to follow your own path. I never wanted to copy anybody’s work. You always try for some kind of originality, even if it isn’t possible. That’s what I’ve always thought.

MS

Your subject matter is really interesting, and the ways in which you find inspiration, for want of a better word. For example, in the Otways works, the William Buckley theme came through; the outsider, the escaped convict who lived among the Indigenous locals. It must be pretty exciting when you come across a theme or subject that really draws you?

JS

Yes, it is. Sometimes it takes a long while to realise that but you’re right – it’s very much about retaining your ‘handwriting’ — I always tried to do that.

‘Buckley’s Cave’ 1996

Collection: Geelong Gallery

MS

Well, I suppose you can’t paint any other way. You’ll always end up painting like yourself.

JS

That’s right. When I did a series of paintings, whether they were from Antarctica, or Mount Lowell in Tasmania, or some of the other places, I always had a father figure.

For Mount Lyell I had Robert Sticht, who was chief metallurgist in Queenstown in the late 1890s. He was a very eccentric character. A mining boss, but also quite sophisticated. He was a man of some culture. He had a Rembrandt print and a priceless private library. I’ve always been attracted to characters like that.

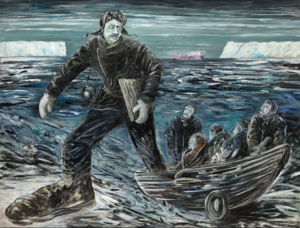

There were two people from the Antarctic. One was Carsten Borchgrevink. He was a schoolteacher in country New South Wales at the turn of the century. But he was also a bloke who wanted to go down to the Antarctic. He ended up getting on a whaling boat as a sailor, bound for Antarctica. At this point no one had set foot on Antarctica – a lot of people had come close. When Borchgrevink who was rowing a boat with an advance party realised he was coming close to the land, he jumped out and said, ‘I’m the first human being to put foot on Antarctica’. His captain pulled him back straight away, but Borchgrevink was a hero. He was a difficult man, very awkward, but he had this madness about him which I found very attractive.

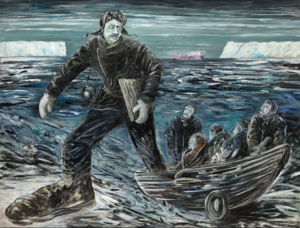

Borchgrevink’s foot (1987)

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas , 197 x 156cm

After that first trip, he gathered a team together and went down to the Cape Adare area. They stayed there for a year, so he was among the first to stay for an extended time as well. He was a real outsider. I’ve always loved mavericks like that. Despite Borchgrevink’s success, the British ignored him completely because he wasn’t part of the Establishment, not part of the Royal Scientific Society and all that, he was just a loose cannon. But before that he beat Scott to the South Pole. He also stayed with Amundsen. In retirement Borchgrevink was finally given some sort of recognition, the British Royal Society medal – bugger all, really!

I got a sense of what inspired Borchgrevink when I went to Antarctica myself. A couple of helicopters used to drop us off right in the middle somewhere, in the most remote expanse. And you sat there in the evening with a glass of whisky in your hand, thinking, ‘I’m really away from the world’, that sort of feeling.

MS

Amazing. I imagine the stars were really bright.

JS

That’s right – and also the southern lights, Aurora Australis. At 10 o’clock one night on the Icebird we were all down in the hold drinking and I went on the deck just to get away from all that – and I saw this massive white yellow streak going right across the sky, like a big question mark. The others came out and we stood around in awe.

MS

You know one of the paintings I liked from Antarctica was the one where your fellow artist Bea Maddock is being lifted onto the boat. She’d broken her leg and you painted her being winched aboard?

JS

Yes, poor Bea. She’d barely made it to shore when she slipped. For the rest of the trip she could only sketch from the boat.

MS

That would have been pretty rough being on a boat for weeks not being able to move around.

JS

Yeah, she was very stoic. The isolation was tough even without an injury like that. This was back in the days with the old radio systems – no phones, so to make contact with your family or anyone else you had to book in and you could talk for 10 minutes on the bridge and that was it.

‘Bea Maddock being lifted onto the Icebird- Heard Island’ 1987

Collection: State Art Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth

MS

So you would have really felt cut off from the rest of the world just on this solitary ship. And back home, as far as your regular routine goes, have you always worked five days a week or does that vary?

JS

Probably five days a week. On Saturdays I could be found sort of floating around the house, or maybe having a punt on the horses or watching a bit of footy. I’m very ordinary! (laughs)

MS

(laughs) I don’t know if ‘ordinary’ is the right word, Jan. When I look around this studio and see how much work you’ve done over the years the thing that strikes me is that you have created so many huge works over your life. You didn’t muck around. You had an idea and you executed it.

JS

Yeah, that’s generally true.

MS

I suppose using acrylics is quite good for that?

JS

Yes, acrylics are good for large-scale painting. When I was doing some smaller work I’d use oil. But what I found was that I’d use acrylics so close to oil that people don’t know.

MS

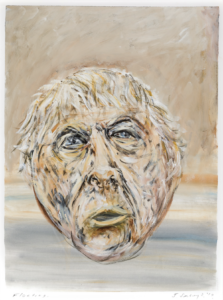

Let’s talk about work you’ve done more recently. When I was supposed to first see you two years ago, before COVID intervened, your show with Niagara Galleries was on, called ‘Not Quite the Last Picture Show’ . You had a self-portrait in that and I thought, wow, I hadn’t seen a lot of self-portraits by you. Although, speaking to your wife Helen, she said that you actually do self-portraits from time to time.

JS

In secret (laughs).

MS

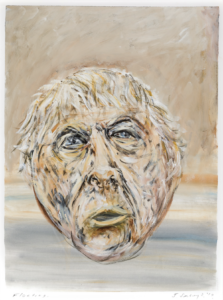

Well, I thought that one in the show was great. It was called ‘Floating’ and it was basically a head disembodied – there was no neck even.

JS

That’s right. That was the intention.

MS

Can you tell me about that?

JS

It was because I wanted some sort of figurative element for the show. I was hoping to do a bigger one but then when I did it I thought, ‘That’s enough.’ I’ve done other self-portrait drawings and so on, but portrait painting is another thing, a special thing.

‘Floating’ 2019

Acrylic on paper, 68.5 x 51cm

MS

Do you like it?

JS

I like it, yeah. There are some good portrait painters – people like Rick Amor, fantastic painter. There are quite a few in Melbourne.

MS

Yeah, Rick Amor is amazing.

JS

But the thing is with the art scene there’s a lot of intellect – the new way of making art. You get all these sort of sharply designed things, bold colours and everything else, but at the same time I think they have a limited life. The photographic image is good, but I think painting is better, though it depends what the painting depicts. Every week when you read the reviews – not that there’s many reviews anymore – you see the fascination with a method, a technique, and not enough of what it’s actually saying.

I always thought that anything is valid providing you’re not overcome by the wonderment of technique. I still believe you can be very avant garde just being a painter. Just painting. It’s your life in a way. It’s done by hand.

MS

Totally. It’s becoming more and more valuable and valued because we are bombarded by so many digital images and photographic images that this idea of putting paint on a surface, it’s becoming more rare.

JS

That’s right. When you’re growing up you’re learning all about art, modern art and so on, it’s all part of it, but at the same time you’re always looking for some odd character that’s coming up.

MS

You’ve held lots of very important positions over the years. We talked about your position at ANU. You were also appointed visiting chair in Australian studies at Harvard University, which was I think the first time an artist was appointed to that position. And you were a trustee of the National Gallery Victoria. You’ve been bestowed the highest award at RMIT, the Doctor of Arts, and you’re one of the leading artists in Australia. Yet you’re so modest, Jan. How have you been able to keep your feet on the ground over all these years?

JS

Well, I don’t know about modest. The thing is you do these things – and I’ve never asked for this to happen – people just gave them to you. Harvard, for instance, there was never an artist in that position, it was always high-class academics. I’d never been to university and here I was going to the top university in the world! (laughs)

MS

(laughs) What was that experience like?

JS

Marvellous, but tough. The students at those universities are very, very eager and I found myself doing quite a lot of talks on Australian art. When I went there I thought, ‘What the hell have I got to do here?’ and then Harvard said, ‘Jan, could you arrange an Australian art show?’ So I started asking around about borrowing all sorts of art. It was all going to take so long. Then when it all looked impossible we got the Holmes a Court collection, a very distinguished collection of Aboriginal art from various parts of Australia. And that was part of my mission – to show Australian art.

MS

You were saying to me before that you’re probably not going to return to painting at this stage. Have you decided definitely?

JS

Well, it’s rather hard for me, having this ailment, it’s harder to set up.

MS

Are you still drawing?

JS

Yeah, I’m doing some drawing. But you see I’m at the end of things – this is my studio, this is the place I built over the years. I mean, (my wife) Helen and my daughter Jes are doing a great job cataloguing my stuff, but it’s not a working studio anymore.

MS

It’s a pretty special space. I’ve seen a lot of studios over the years since I’ve started this podcast. And I’ve got to say this one is probably in the top three, if not number one – it’s just wonderful.

JS

Yeah, it’s a special workplace.

MS

Well Jan, I’d like to thank you for your time today and for sharing your story and your extraordinary work in this amazing space. Thank you so much.

JS

Thank You.

Melbourne

August, 2022

https://youtu.be/XhGHEkABcjc?si=yaDOc7AgrCAe7sRA

159 قسمت

Manage episode 388546878 series 1255162

Above photo of Jan Senbergs by Riste Andrievski

Click play for my podcast introduction to this interview and scroll down for the transcript.

Podcast listeners click here and scroll down for transcript.

Watch the YouTube video of Jan Senbergs’ studio and work here

Links

- Jan Senbergs’ website

- Jan Senbergs on Instagram

- Jan Senbergs at Niagara Galleries

- Talking with Painters YouTube channel

- Talking with Painters on Instagram

- Talking with Painters on Facebook

- Subscribe to the TWP newsletter

- PDF version of transcript for tablet/desktop

With over six decades of work as a painter, printmaker and draughtsman, leading artist Jan Senbergs has exhibited in over 50 solo shows and has been the subject of three survey shows including a major retrospective curated by the National Gallery of Victoria in 2016. A rare accomplishment.

His art evolved from early masterly screenprints to large scale paintings and with subject matter as varied as urban and natural landscapes, industrial themes, surreal structures and forms and aerial map-like works.

This episode has been a long time coming. Covid threw out our plans for an early 2020 meeting but two years later we met in Jan’s inspirational studio in Melbourne. His voice has been affected by some health issues and so this episode is coming to you by way of transcript (below) and an intro on the podcast.

As I was setting up my audio equipment on the day of the interview, Jan and I chatted about the time he had spent in London in his 20s. We talked about other Australian artists who were there at that time. That’s where the recording of the interview began.

Jan Senbergs

I was the younger artist who came into that area and I didn’t know anybody. I didn’t want to bother the local Antipodeans (laughs) so I usually went out by myself. I headed for the National Gallery on one occasion and ran into Arthur Boyd heading there too. We travelled together on the bus from Pimlico to Trafalgar Square. It was very nice because we walked through the Gallery making comments. It’s lovely to do that with another painter. We walked past one room and Arthur stopped and said, ‘There’s a good painting in this room.’ It was a big dog watching over a dying nymph, by Piero di Cosimo. He was such an interesting painter. Afterwards, Arthur suggested we go and have a drink, so we went across the road and had a couple of beers and then he said ‘You’ll have to excuse me, but I’ve got to go back home. I’ve got a few duties there.’ We shook hands and I never saw him again.

Maria Stoljar

You never saw him again?

JS

No, but what was nice about it was the generosity of the older person to somebody younger who had just arrived.

MS

How lovely. But you knew a lot of famous Australian artists like Fred Williams, for example. He was a friend of yours, wasn’t he?

JS

Yeah, I knew Fred. When I first started showing around, I mixed with some of the older artists. At that time there were hardly any younger artists around. And because I hadn’t gone to an art school, I was very isolated. It’s quite different for artists today. Now there are thousands of young people trying very hard to make good art after their schooling. It’s a different atmosphere. Schools pump out all these people with hopes and ambitions. That’s the reason it’s good to know some of the older painters.

MS

Yes. Like John Brack?

JS

Yes, John Brack was one … Len Crawford, Fred, Roger Kemp – these were heavy-duty Melbourne blokes.

MS

It’s amazing that you, in your early 20s, were hanging out with those people.

JS

Yeah, it was actually. Because I couldn’t get into art school so I’d started working in a silkscreen printing company, which was a terrible bloody job (laughs).

‘Modern monument in colour ‘ 1975,

Colour screenprint, 56.6 x 81.2cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

MS

Why? Was it heavy work or just dirty work?

JS

Dirty work. Screenprinting was very dirty. It was toxic and unventilated. As an apprentice you’ve got to scrub the screen and so on – you get all the shit jobs (laughs), but that’s understandable.

On Friday nights, though, during the period of the six o’clock closing, I used to go into town. I didn’t want to go with the local trades blokes and drink with them, I’d go straight into Little Collins Street where all the real old lefties hung out – a fantastic atmosphere. They weren’t all painters by any means – there were writers, clapped-out academics and all sorts of people.

MS

Really bohemian.

JS

Yeah, but interesting to me. I went there and I just stood around. They didn’t pay any attention to me, but I was listening. It was an education. A political education as well.

MS

How amazing. So did you keep in contact with those people?

JS

Well, most of them I did, yeah. Including some writers. I was always interested in writing and writers. I used to read a lot when I was younger. The usual standard fare of James Joyce (both laugh).

So I was mixing with all these people at six o’clock closing. There was a frantic atmosphere on a Friday night. There were all these characters coming in from work, and they wanted to have debates and bash out the things that they wanted to talk about. It was interesting.

MS

Yeah, and do you feel like that sort of political leaning comes through in your painting? Do you consciously think about that?

JS

No. I mean, it’s there. How can I put it? I don’t like to be a spruiker for any cause. Your paintings should do that. Usually what happens is that if people are too strident in their political views, they produce paintings which are very single-minded – with a message they want to send, but often the artworks are no good. There’s always been a debate about that, to see how far you can go.

MS

Actually what comes to mind are the ‘Altered Parliament House’ works. Those two works you painted when you were in Canberra. You were there during the dismissal of the Whitlam government in 1975. They’re powerful paintings which are silkscreen and oil. Can you tell me a bit about that time?

‘Altered Parliament House I’ (1976) Synthetic polymer paint and oil screenprint on canvas Collection: National Gallery of Victoria

JS

I was in Canberra at the ANU for a couple of years. What do they call it? Creative Arts Fellowship. They gave me a studio. Students were supposed to come and listen to your wise words but nobody turned up so it was a very easy job (laughs). And a very interesting period because at that time the Whitlam Government was introducing Medicare. I used to go to Parliament House and sit listening to Question Time. I’d wander up there out of curiosity, to see what they were talking about – to see how they were misbehaving (laughs). It was fascinating, it was lively. Then the day came when Gough was overthrown. The two paintings I did were of Parliament House (the Old Parliament House). They were sort of on a dark ground. It was nighttime. I was living in Campbell which crossed Anzac Parade and in the distance you could see this white ghost-like structure that was Parliament House. It gradually became a kind of symbol, or the anchor, for the paintings. They’re about as close as I’ve ever been to a political painting – I like to leave that sort of thing with a suggestion rather than hammering it down somebody’s throat.

MS

I think one is in the National Gallery of Victoria and the other is in the National Gallery in Canberra. With respect to number one, in the foreground there are ruins and so it’s like a metaphor for the destruction of the whole parliament in a way?

JS

Yeah, it did have those suggestions. Everybody was very keen on what was happening politically at the time and so you didn’t need to sort of push your point. Politically, I’ve been towards the left all the time, but at the same time I’m very critical and I’m becoming more critical as I get older! (laughs)

MS

What I find interesting about your work is the fact that you started off in silkscreen printing and even though you let that go by about 1980 or so, you started incorporating that into your painting.

JS

That’s true, yeah.

MS

That sounds like a quite laborious thing to do.

JS

It was a shocking thing. I hated it by the end of it. (laughs)

MS

(laughs) Did you? Why?

JS

Oh, it was so laborious to get things right, setting up the registration over large areas. It was very hard work. It wasn’t like when you’re painting or doing a drawing. When I came back from Canberra, I was doing screen prints and I felt at that stage that I was getting a bit too sophisticated with the prints – too much of a smartarse (laughs) – so I gave it away.

‘The flyer’ 1975

Synthetic polymer paint, oil screenprint on canvas, 167 x 244cm

Collection of Paul Guest, Melbourne

MS

I think by that time you were being called ‘the greatest silkscreen printer in Australia’. Maybe that was when you felt like you had had enough?

JS

Well, I don’t know about that. But what I wanted to do was to make a mark again, go completely the other way. So I began to draw. And I started to draw around Port Melbourne, especially old Port Melbourne. I gradually changed.

Port panorama, 1980, lithograph, printed in black ink on white BFK Rives Moulin du Gué paper

45.4 x 63.4 cm image; 57.0 x 76.0 cm sheet

Collection: Art Gallery of NSW

MS

So that was quite an industrial sort of landscape?

JS

Yes. And that was also around the time that I met my second wife Helen Beresford.

MS

Yeah.

JS

All of these things – it was a very exciting time.

MS

It must have been a really big change in your life.

JS

It sure was, yeah.

MS

And it was around that time that you got that huge commission to create a work for the High Court of Australia. I think you were involved from the very beginning when they were designing that building. Just to give a bit of background – the High Court of Australia is a great example of brutalist architecture. We’re talking about huge concrete walls, big open spaces, and the area that you had to create a work for was quite a large area.

JS

In the atrium, yeah.

MS

So how did you go about that?

JS

They had a shortlist of about four or five when they gave me the job. I think they probably gave it to me because I’d realised it was too huge an area for canvas – it would sag within a couple of years – so I’d thought of some other material. I started through theYellow Pages to look for materials. I didn’t get very far! I spotted ‘aluminium’. That was it! (laughs) Aluminium was light and it was permanent, you had to anodise it, it wouldn’t corrode.

Constitutional Wall Mural and States Wall Mural 1977 – 80

Collection of the High Court of Australia

MS

Had you ever used it before?

JS

No

MS

So this was a totally new technique that you were going to try?

JS

That’s right. I had a friend, Ian Claremont, who knew about anodising. It was all a bit unexpected. I told the story of the Constitution of the High Court, the States and the Supreme Court with images etched into the aluminium.

MS

So the brief was basically to depict imagery about the Commonwealth and the six states. Is that right?

JS

They didn’t mention the six states but that became part of it. I introduced that.

When I first got the job, I knew nothing about the High Court and I wondered ‘What the hell am I going to do? What sort of design?’

MS

(both laugh) Well, I think before the building was built, the High Court was sitting in Melbourne and Sydney. There was no building in Canberra?

JS

That’s right. The High Court had rooms in every state – small rooms, chambers. In order to find out more about what the function of the court was, I was lucky enough to meet Ninian Stephen, who used to be the Governor-General and a High Court Judge. I asked him if I could come and see him to explain what the functions of the High Court were.

MS

(both laugh) Well, I mean, when you think about it, the layman wouldn’t know what the High Court did.

JS

Ninian Stephen was so tolerant and kind to me. He carefully explained how the High Court worked. Then I had to design it. The logistics alone were a challenge. I was worried the whole thing would slide off the wall – so I designed these boxes and I screen printed images on them. There was the Constitutional wall and the States wall, shooting all the way up to the top.

MS

And how did you come up with the imagery? What were you looking at?

JS

Well, by that time I was looking at various symbols of Australian institutions. In the case of what I call the States wall, I had all sorts of symbols from each state. For example, Queensland had a tropical industry, sugar cane, which told a story. The larger Constitutional wall was to do with things from the time of Federation when Australia became a state in its own way – a changeover from the British way – so there are a lot of images there. And they liked it (laughs). I found an anodising factory in Melbourne. When it finished for the day, Ian and I would go there through the night and etch the big aluminium sheets in huge acid baths before the factory began its morning shift.

MS

It’s fantastic and it’s still there, obviously. And I think the Queen came when they opened the High Court, and didn’t you have an exchange with her?

JS

I did, actually. When we finished the job and the time came to open it, we were all lined up and the Queen and Prince Philip came along, with the Chief Justice Garfield Barwick introducing us. When the Queen got to me she looked up at my piece and she said, ‘My, that’s big.’ I said, ‘Yes, Ma’am’. The Duke was about four paces behind, and he came up and said, ‘Do you do this kind of thing often?’ and I said ‘Whenever I can’ (laughs). So that was my meeting with the Queen and the Duke.

MS

(laughs) That is a pretty amazing story. So let’s talk about other works of yours that I’ve found interesting. And one of them was when you went to Antarctica. What was that trip like?

JS

It was marvellous, wonderful. It was back in 1987. We went down with the Australian Antarctic Division’s resupply ship MV Icebird. It sailed out to Heard Island and delivered food and supplies to the Davis and Mawson stations. That was the main intention of the trip. It was marvellous too on all sorts of levels. The Antarctic landscape is fantastic and it’s been photographed a million times, but my angle was a bit different. I was fascinated with life down there and how we are squatting on another continent with our suburban values. My paintings were more about the bases than the icebergs.

MS

And you had two major paintings, ‘Mawson’ and ‘Davis’, depicting those bases down there where you gave us that aerial perspective that you’re very well known for – those map-like paintings. These aren’t the same as your more urban pictures but it’s that sort of feel, of an aerial perspective. And with all that ice in the background, these are very dramatic paintings.

‘Davis’ 1987

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas

213 x 289cm, private collection

‘Mawson’ 1987

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas

213 x 289cm, private collection

JS

Yes, the ‘Mawson’ painting is like that. You’ve got this settlement right on the edge with a huge dome of Antarctica behind it. I exaggerated it. There was a kind of map-like painting of a base as well as a huge amount of rubbish lying about. Part of the job was to pick up some of the rubbish and go and put it back on the ship and take it to a quarry in Tasmania.

MS

Oh ok, I didn’t realise that. That’s interesting because that idea of detritus and waste, that’s something that often appears in your work. Is that something that attracts you – those forms?

JS

I start off with images that I want to use. Then I apply some of them to paintings. It’s a combination of thinking. It’s hard to explain. It’s a kind of storytelling, only in a less obvious way. Firstly, I paint a quality of imagery, before I start telling the story–you know, that’s important. With Davis and Mawson, I wanted details of various things that I wanted to add to the composition – a bit like early Chinese landscapes that are taken from various levels – unlike the Western view on a fixed level. So you have various points of viewing all crisscrossing that make up the composition which you in turn take to the next step to make it interesting.

MS

Yeah. Would you start with a sketch to determine the composition?

JS

Yes. But also I had notebooks. I’d do sketches there. They were mostly sketches from memory. Plein air ones as well of course.

MS

And when you’re working on a big painting, do you ever decide halfway through ‘this isn’t working, I’ve got to change it’. Does that happen often, or have you really predetermined it before you start?

JS

You mean the composition?

MS

Yes.

JS

Sometimes. Sometimes you fail and you start from scratch again. But not often. For me, a lot of these canvases are like maps. I’d worked out the scale, the relationships. There’s a lot of fiddling around with map-like imagery early on.

‘Melbourne capriccio 3’ (2009)

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 195.2 x 184cm

Collection: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

MS

I’d like to jump back now – so in 1966 you were awarded the Helena Rubinstein Travelling Art Scholarship and you went to Europe. You stayed in London for a while and then when you came back in the late 1960s, things had changed in the art world hadn’t they?

JS

They sure had, yeah.

MS

Can you tell me a bit about that? I think all the rage was colour field painting, hard edge abstraction …

JS

That’s right. When I came back there was this new type of thing here and so I wanted to show some of the smart tricks I learnt in London (laughs)

MS

(laughs) So, you found that you changed direction a little bit over that period?

JS

Yeah, I realised that my previous paintings were too clogged up, too rich sometimes, and also crude. I didn’t mind the crudeness but it was time to leave that. I’d grown up a bit (laughs). I made some steel sculptures, a kind of gesture at outdoor art, minimal art.

MS

They were quite geometric, weren’t they?

JS

Yes, standing on legs. They were about 20 feet tall. I made them in my backyard. I left the final processes to the fabricator but I made the design, a kind of slot to hold this image of a head, but the problem was the image was too top heavy (laughs).

MS

So they didn’t stay up?

JS

They stayed up for a couple of years, in St Andrews, in the hills north of Melbourne. I found some land to put this stuff on and met Cliff Pugh, who lived up there. He said I should contact Frank Dalby Davison. Dalby Davison was a very controversial and interesting writer in the ’30s, being ahead of the game and writing about people’s relationships. He agreed to put them up on his land, and I said I’d try not to make a mess (both laugh). I made five of these sculptures and dug a ditch and put them in concrete and left them there. You could see them from the road down below the hill and people were wondering what the hell they were.

MS

They looked sort of alien?

JS

Yeah, some people thought they were guideposts for planes coming in. People came up with all sorts of explanations for them.

MS

Isn’t that the definition of great art? To get people to wonder and to use their imagination.

JS

Exactly, yeah, that’s right. They stood up there for a while and then one day there was a huge storm and they blew over. Also, the cows didn’t help. Frank Dalby Davison had a lot of cows and they were leaning against the sculptures, causing them to topple, and I thought that was very unfair for Frank (both laugh).

MS

That’s a shame, but at least you’ve got images of them.

JS

Yes. I went back and saw Frank and said, ‘You’ve been very generous’.

MS

I bet he missed them because they would have been like a real statement on his property.

JS

Well, it could have been that. I suppose I was one of the first people doing that sort of thing in Australia. The Americans did that sort of land art– Robert Smithson and a couple of others, but in different ways. I had always wanted to do something outside of painting.

MS

And 3D obviously as well. But you didn’t continue to do a lot more of that sort of sculptural work?

JS

No, I stuck with the brushes.

MS

I want to take you back to when you first got to Australia. You had a rough time during the war years. What was it like when you got here?

JS

We left Latvia, ending up in the British sector after the war, in a DP (Displaced Persons) camp. We stayed there for about four or five years. And finally, we got boats to Australia. Nobody knew anything about Australia. For example, my grandmother who was with us carried a ham that she’d cured because she thought that in Australia there’d be no food (laughs). When she got off the ship the Customs officers took the ham. She was so upset – ‘They’ve taken away my food!’ (laughs). We were hauled off to Bonegilla, the migrant camp near Albury-Wodonga. It was an old army camp. All the adults were moaning and groaning but us kids loved it. I’d just turned 10 so I was very happy. It was like we were released from some dark place to this wonderful sky and golden grass, to muck around and enjoy all of it.

MS

So it was a very optimistic experience coming to Australia for you. You couldn’t speak English at that point?

JS

No. We lived there for about four months – my sister, mother, grandmother and I. The camp had people from all sorts of countries. We went to a one-teacher primary school for young farming kids – there were only about eight students. I often wonder how the local kids must have felt – their lovely little school invaded by hundreds of little wogs! (laughs)

MS

(laughs) What experience did you have with art at that point? How did you become interested in art?

JS

I was always drawing as a child. I went to trade school in Melbourne, at Richmond Tech – but I wasn’t at all interested in trades. I started to do little sketches in my exercise book. One day Len French the painter came to the school as a rookie teacher. He was a terrible teacher (laughs), but he used to liven the place up. One day he brought in three postcards: One was of saints, by El Greco, one was Cezanne’s ‘Mont Sainte-Victoire’, and the third was ‘The Sleeping Gypsy’ by Henri Rousseau. Len said, ‘Which one do you like?’. I liked Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy. And that triggered something in me because I began to realise that there was this other big world out there.

MS

He must have been a very exciting person to come into your life.

JS

He was, yeah.

MS

Was he an established painter at that point?

JS

No, he wasn’t. He was becoming established – he ran with the local scene. A couple of years before that he’d been overseas, he’d done a bit of travel, so he was sort of sophisticated.

MS

And he became a mentor for you for many years?

JS

He was in a way. He introduced me to the pubs (both laugh).

MS

Is that how you got to meet John Brack and Fred Williams and the other artists in Melbourne?

JS

The way I met John Brack was different. I had a studio in Hardware Lane – one of the lanes of Melbourne. It was an awful place, very dark and dingy, and I was doing these black, ugly pictures that nobody could possibly want (laughs). One day in walked John Brack with a bloke called Hal Hattam. He was a doctor who hung around with the artists and was a bit of a collector as well. Brack was very austere and firm, and I was like a rat scurrying around. They didn’t say much, just looked around and then left. But about two weeks later I was asked to drop a painting off at John Brack’s house – he’d bought one of my paintings. I was so touched.

MS

Wow.

JS

Because coming from him it was so special.

MS

Yes, and that’s before you actually got to know him?

JS

Yeah, he liked my stuff.

MS

He was a lot older than you, like 20 years older?

JS

He was, yeah. He came out of the army without firing a shot and then he became a teacher in Melbourne and got a job at the Gallery School at the NGV. He ended up teaching at Melbourne Grammar – all the little rich boys. (laughs)

MS

Well, they have to be taught too (both laugh).

JS

John Brack was a big influence on me because he was the conscience of our generation. Later, we shared the same dealer, Rudy Komon, who was my dealer in Sydney. George Baldessin was also with Rudy. As was Fred Williams. A bit of a boys’ club.

MS

Well, I suppose in those days there were fewer women artists. But that must have been a pretty amazing thing for you because Rudy Komon was one of the most influential art dealers in Australia at the time. He got you on his books when you were in your mid 20s I think?

JS

Yes, I was.

MS

That’s amazing.

JS

He was planning to give me a first show. But I’d gone and made a mess of myself – I sort of spoiled it all – I smashed myself up in a car accident. Went through the windscreen and almost lost an eye. Rudy came into the hospital and saw me and as he walked out, he said to someone, ‘Well it’s a pity about Jan, he could have been a good artist’ (laughs), and I said ‘Don’t say that!’

MS

I can imagine you didn’t want to hear that at that time. That didn’t happen in the end, thankfully!

JS

Years later when Rudy and I travelled around the place I sometimes raised that: I said, ‘Rudy, you almost wrote me off – you told me I was no good!’ He said ‘Oh, I wouldn’t do that to you.’

MS

So, you were with him for 20 years or so?

JS

Close to it yeah. He was quite different from the other dealers. He gave money to various painters from his stable.

MS

Like a wage sort of thing?

JS

Yeah, to keep them going. Rudy also had Jon Molvig from Queensland. Molvig would ring up Rudy and say, ‘Rudy I need some dough- not just some dough – the full symphony’. He was very keen on Molvig.

MS

And Rudy had a lot in common with you, didn’t he? Because he was also a migrant.

JS

He was, yeah. Though he never talked much about his past.

MS

He was a lot older than you.

JS

Oh, yeah. He was an interesting character. The first time I showed with him was in the ’70s. I was in a drawing show. When I came in from Melbourne to the gallery and saw red stickers everywhere. I said, ‘Rudy, Jesus! You mean all these people bought my drawings?’ and he said, ‘Oh yes, Jan, there are a few people who like you.’ But who they were he wouldn’t say. Years later, after he died, I was at Rudy’s gallery with Gwen Frolich. She was Rudy’s rock. She’d pulled him out of problems time after time – tax problems and all the other stuff – and she and I were looking through Rudy’s storeroom. We were digging through all this stuff when I came across one of my drawings. Then I found more of them, all from that first drawing show. And I said to Gwen, ‘What’s the story?’ Gwen just smiled and drew on a cigarette. She said, ‘Rudy thought you needed some money at the time.’ Rudy had bought up my drawings!

MS

And he did it that way so that it bolstered your confidence as well.

JS

Yeah, he was a good bloke. But he was full of bullshit as well (both laugh).

MS

Well, anyone in the art world has to be a bit like that don’t they?

JS

Yeah. I once travelled with him to South America, to the Sao Paulo Biennial, in which I was representing Australia. We went on this trip with James Gleeson.

MS

The famous surrealist painter.

JS

Yes, that’s right. Gleeson’s partner, Frank O’Keefe, wanted to go as well so it ended up being the four of us on a plane to Brazil, via Tahiti. Rudy wanted to go as our representative, but he really just wanted to be there for the trip.

MS

So for that 1973 Sao Paulo Biennial I understand you did 18 large paintings over two years. Those works were very typical of what you were doing at the time, those bleak industrial landscapes, very large works?

Fort 2 (1973),

152 x 183cm synthetic polymer paint, oil screenprint on canvas

Collection: National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

JS

Yes, that’s right.

MS

And I think Fred Williams called you an ‘industrial surrealist’.

JS

(laughs) Yeah.

MS

Those structures and forms that are in those paintings – for example, ‘Fort 2’ – they do have quite a surreal quality to them. They don’t exist in the world. How did you come to paint those images?

JS

I was just starting to use silkscreen techniques in a painting, which straight away made everything much sharper. Even though you might have very dark colours, blacks and browns, there’s movement within those colours. People picked up on an industrial theme. People have sort of pigeonholed me as an industrial landscape artist. I’m not just that, I’m a lot of other things at the same time. But they like to label you – it’s always the case.

MS

Yeah. For example, those Antarctic paintings are totally different. Actually, those works where you were painting near your holiday home around the Otway Ranges in south-western Victoria, they’re also really beautiful works, and very expressive paintings.

‘Otway night’ 1994

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 198 x 259cm

Collection: Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney

JS

I’m glad you like them.

MS

And you know what I noticed about those and also the map paintings, those aerial paintings – they have much more colour. Did you find that you were using more colour later in your career?

JS

Yeah, I think so. I was slowly moving away from what I call my ‘axle grease’ period.

MS

(laughs) Which I liked as well.

JS

But you’re right. The colour change is there in the Otway paintings. It’s not over the top, but it’s there. I suppose as you get older you don’t have to hammer everything every time. You learn how to just step back, to retain your point. When you’re younger you’re fierce and attacking. As you get older it doesn’t matter so much. I’m finding that with me these days. I’ve had a very good run when I come to think of it – all the things that I’ve had the opportunity to do. It’s been marvellous. I’ve had the chance to do my own imagery, and I have always wanted to be outside the main movement. Maybe close to the movement sometimes, but not part of it.

MS

Why do you think that is?

JS

Must be my twisted nature (laughs).

MS

Yeah, well, I’m going to be a psychoanalyst now. Is it partly due to coming to Australia when you were 10, and not going to art school, not doing the traditional thing that somebody who was born here might have done?

JS

Yeah, sure. You become very aware of that of course, but you still want to follow your own path. I never wanted to copy anybody’s work. You always try for some kind of originality, even if it isn’t possible. That’s what I’ve always thought.

MS

Your subject matter is really interesting, and the ways in which you find inspiration, for want of a better word. For example, in the Otways works, the William Buckley theme came through; the outsider, the escaped convict who lived among the Indigenous locals. It must be pretty exciting when you come across a theme or subject that really draws you?

JS

Yes, it is. Sometimes it takes a long while to realise that but you’re right – it’s very much about retaining your ‘handwriting’ — I always tried to do that.

‘Buckley’s Cave’ 1996

Collection: Geelong Gallery

MS

Well, I suppose you can’t paint any other way. You’ll always end up painting like yourself.

JS

That’s right. When I did a series of paintings, whether they were from Antarctica, or Mount Lowell in Tasmania, or some of the other places, I always had a father figure.

For Mount Lyell I had Robert Sticht, who was chief metallurgist in Queenstown in the late 1890s. He was a very eccentric character. A mining boss, but also quite sophisticated. He was a man of some culture. He had a Rembrandt print and a priceless private library. I’ve always been attracted to characters like that.

There were two people from the Antarctic. One was Carsten Borchgrevink. He was a schoolteacher in country New South Wales at the turn of the century. But he was also a bloke who wanted to go down to the Antarctic. He ended up getting on a whaling boat as a sailor, bound for Antarctica. At this point no one had set foot on Antarctica – a lot of people had come close. When Borchgrevink who was rowing a boat with an advance party realised he was coming close to the land, he jumped out and said, ‘I’m the first human being to put foot on Antarctica’. His captain pulled him back straight away, but Borchgrevink was a hero. He was a difficult man, very awkward, but he had this madness about him which I found very attractive.

Borchgrevink’s foot (1987)

Synthetic polymer paint on canvas , 197 x 156cm

After that first trip, he gathered a team together and went down to the Cape Adare area. They stayed there for a year, so he was among the first to stay for an extended time as well. He was a real outsider. I’ve always loved mavericks like that. Despite Borchgrevink’s success, the British ignored him completely because he wasn’t part of the Establishment, not part of the Royal Scientific Society and all that, he was just a loose cannon. But before that he beat Scott to the South Pole. He also stayed with Amundsen. In retirement Borchgrevink was finally given some sort of recognition, the British Royal Society medal – bugger all, really!

I got a sense of what inspired Borchgrevink when I went to Antarctica myself. A couple of helicopters used to drop us off right in the middle somewhere, in the most remote expanse. And you sat there in the evening with a glass of whisky in your hand, thinking, ‘I’m really away from the world’, that sort of feeling.

MS

Amazing. I imagine the stars were really bright.

JS

That’s right – and also the southern lights, Aurora Australis. At 10 o’clock one night on the Icebird we were all down in the hold drinking and I went on the deck just to get away from all that – and I saw this massive white yellow streak going right across the sky, like a big question mark. The others came out and we stood around in awe.

MS

You know one of the paintings I liked from Antarctica was the one where your fellow artist Bea Maddock is being lifted onto the boat. She’d broken her leg and you painted her being winched aboard?

JS

Yes, poor Bea. She’d barely made it to shore when she slipped. For the rest of the trip she could only sketch from the boat.

MS

That would have been pretty rough being on a boat for weeks not being able to move around.

JS

Yeah, she was very stoic. The isolation was tough even without an injury like that. This was back in the days with the old radio systems – no phones, so to make contact with your family or anyone else you had to book in and you could talk for 10 minutes on the bridge and that was it.

‘Bea Maddock being lifted onto the Icebird- Heard Island’ 1987

Collection: State Art Collection, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth

MS

So you would have really felt cut off from the rest of the world just on this solitary ship. And back home, as far as your regular routine goes, have you always worked five days a week or does that vary?

JS

Probably five days a week. On Saturdays I could be found sort of floating around the house, or maybe having a punt on the horses or watching a bit of footy. I’m very ordinary! (laughs)

MS